Isa Whitney, brother of the late Elias Whitney, Principal of the Theological College of St. George’s, was addicted to opium. He developed a habit, as I understand, when he was at college. He found, as so many people before him, that it is easier to start than to stop smoking it, and for many years he continued to be a slave to the drug, and his friends and relatives felt horror and pity for him at the same time. I can see him now, with yellow, pale face, the wreck and ruin of a noble man.

One night my door bell rang, about the hour when a man yawns and glances at the clock. I sat up in my chair, and my wife laid her needle-work[1] down and made a disappointed face.

“A patient!” said she. “You’ll have to go out.”

I sighed, because I’ve just come back from a hard day.

We heard the front door open, a few hurried words, and then quick steps upon the linoleum. Our own door opened, and a lady, dressed in dark-coloured clothes, with a black veil, entered the room.

“Excuse me for coming so late,” she began, and then, suddenly losing her self-control, she ran forward to my wife and sobbed upon her shoulder. “Oh, I’m in such trouble!” she cried; “I need help so much!”

“it is Kate Whitney,” said my wife, pulling up her veil. “How you frightened me, Kate! I had no idea who you were when you came in.”

“I didn’t know what to do, so l came straight to you.” It was always like that. People who were in trouble came to my wife like birds to a light-house.

“It was very sweet of you to come. Now, you must have some wine and water, and sit here comfortably and tell us all about it. Or would you like me to send James off to bed?”

“Oh, no, no! I want the doctor’s advice and help, too. It’s about Isa. He has not been home for two days. I am so frightened about him!”

It was not the first time that she had spoken to us of her husband’s trouble, to me as a doctor, to my wife as an old school friend. We tried to find the words to comfort her. Did she know where her husband was? Was it possible that we could bring him back to her?

It seems that it was. She had the surest information that lately he had used an opium den in the east of the City. So far his absence had always been limited with one day, and he had come back, twitching and exhausted, in the evening. But now the spell had been upon him eight-and-forty hours, and he lay there, doubtless among the dregs of the docks, breathing in the poison or sleeping off the effects. There he could be found, she was sure of it, at the Bar of Gold, in Upper Swandam Lane. But what was she to do? How could she, a young and modest woman, come to such a place and pluck her husband out from among the dregs who surrounded him?

* * *

There was the case, and of course there was only one way out of it. Could I accompany her to this place? And then, as a second thought, why should she come at all? I was Isa Whitney’s doctor, and so I had influence over him. I could do it better if I were alone. I gave her my word that I would send him home in a cab within two hours if he were indeed at the address which she had given me. And so in ten minutes I left my armchair and cheerful sitting-room behind me, and was speeding to the east in a cab on a strange commission, as it seemed to me at the time, though the future only could show how strange it was to be.

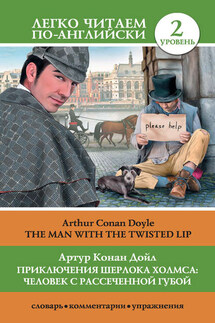

But there was no great difficulty in the first stage of my adventure. Upper Swandam Lane is a disgusting street hiding behind the high docks which line the north side of the river to the east of London Bridge. Between a slop-shop and a gin-shop, there were steep steps leading down to a black gap like the mouth of a cave.[2] There I found the den I was looking for. Ordering my cab to wait, I passed down the steps, with a hollow in the centre, made by thousands of drunken feet. By the light of an oil-lamp I found the door and entered a long, low room, thick and heavy with the brown opium smoke, and full of wooden beds, that reminded me of an emigrant ship.

Through the dark one could notice bodies lying in strange fantastic poses, bowed shoulders, bent knees, heads thrown back, and chins pointing upward, with here and there an eye turned upon the newcomer. The most lay silent, but some muttered to themselves, and others talked together in a strange, low, monotonous voice, their speech began and then suddenly stopped, each mumbled out his own thoughts and paid no attention to the words of his neighbor. At the end was a small brazier, beside which on a three-legged wooden stool there sat a tall, thin old man, with his face resting upon his two fists, and his elbows upon his knees, staring into the fire.

As I entered, a Malay servant had hurried up with a pipe for me, showing me the way to an empty place.

“Thank you. I have not come to stay,” said I. “There is a friend of mine here, Mr. Isa Whitney, and I wish to speak with him.”

Somebody moved and exclaimed on my right, and looking through the dark I saw Whitney, pale, exhausted, and unkempt, staring out at me.